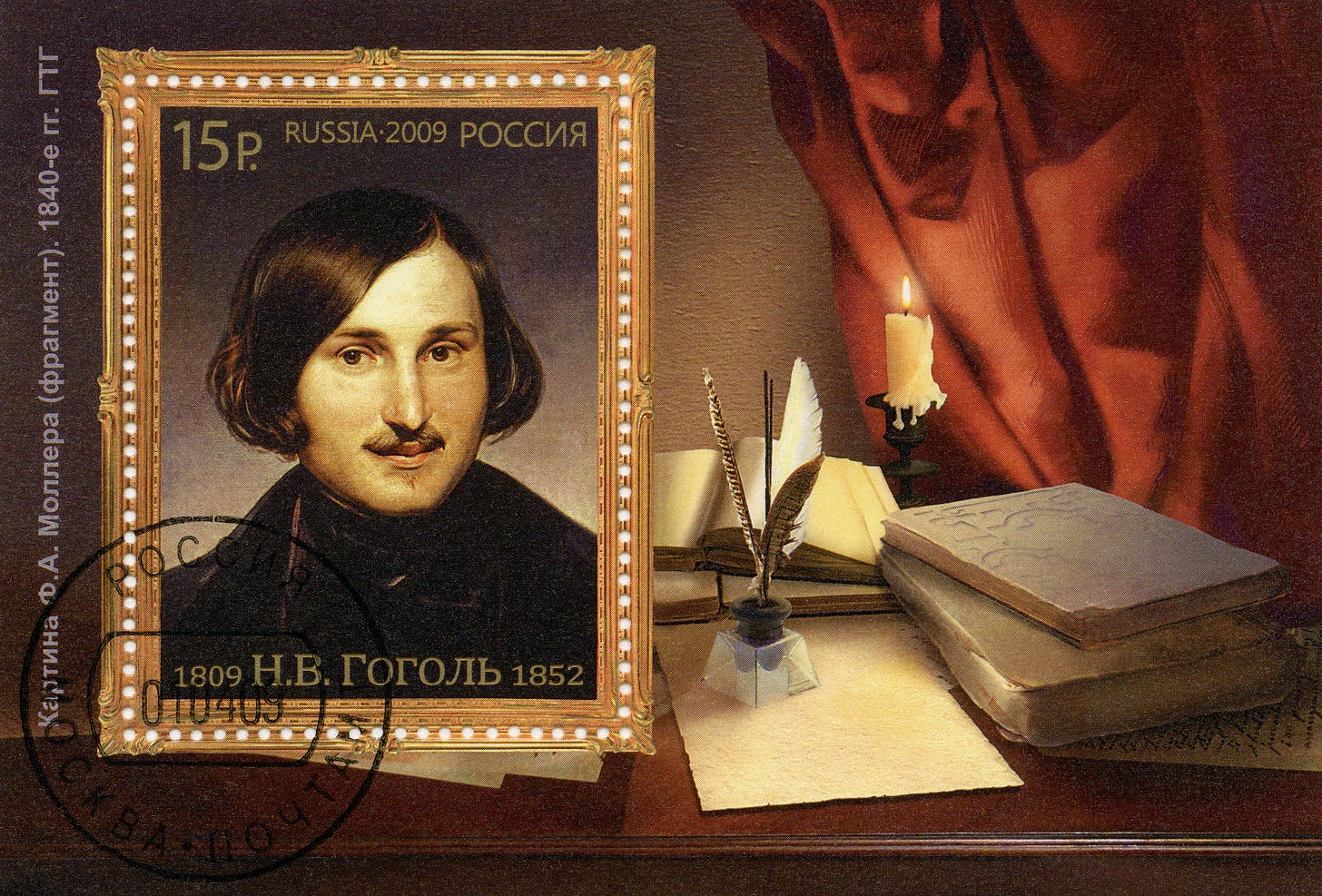

The Anthology of Funny: Nikolai Gogol's "The Nose"

The most perfectly ridiculous story ever written, and the dangers that may ensue from giving it to an impressionable 15-year-old

Nikolai Gogol’s The Nose is a brilliant tale of pompous narcissist who wakes up in Tsarist Russia to find his sniffer missing, only to learn the missing appendage is parading around St. Petersburg in sharper attire than his own. The fatuous hero gives chase, has an anticlimactic confrontation, and looks doomed to life with an “absolutely preposterous smooth flat space” instead of a nose; but order is magically restored after he does nothing ingenious, pays no price for his vanity, and comes to no ennobling insight.

It’s reverse literature! At every juncture where a normal author would write, “And so Major Kovalev, looking back in his loneliness at the error of his previous womanizing ways, resolved to do better…” Gogol just moved to the next insane plot development. A hypochondriacal-foot-fetishist-mystic who was convinced his stomach was upside-down, Gogol was a mess of contradictions. He worshipped authority and was desperate for the approval of censors and royals, but on paper was an incorrigible rule-breaker.

If you can imagine Picasso trying to draw a police sketch, that was Gogol trying to create “positive” or “traditional” literature. Later in life, when he tried to write “uplifting” stories and novels, he was such a complete failure that he went insane with grief, and in one of the all-time gruesome suicides starved himself to death while covered in leeches in a cramped Moscow room. He burned his manuscripts on the way to the next world, punishing himself for a talent he’d come to believe was demonic.

I first encountered The Nose in high school, not long after being taught a good essay began with a summarizing topic sentence, was followed by an expository body, and ended by repeating the first line. In the wake of hearing teachers expound such formulas, I was dazzled by the way Gogol ignored convention, choosing to grow roaring jungles instead of dull gardens.

The best example might be from another of his great tales, The Overcoat, which began, “In the department of…” Every other writer of his age would have continued: “In the Department of Agricultural Acquisitions, situated on Vasilevsky Island, there lived a man named Stepan…”

Gogol went the other way: In the department of… but I’d better not say what department. He abandoned the story at hand and told a different one, about how sensitive government officials are to any department mentioned in any story, recounting as evidence a tale of a police inspector who lodged a complaint with the state, claiming the Tsar’s “sacred name had been taken in vain” after reading a novel in which a policeman “appeared on every tenth page, occasionally, indeed, in an intoxicated condition.”

Violating every rule about maximum economy in prose fiction, Gogol then had to wrap up the absurd saga of the complaining police inspector before he even began the famous story of Akaky, the penniless anti-hero clerk whose quest to buy a new overcoat became the epic challenge of his life.

The Nose is more chaotic. It starts in the home of barber Ivan Yakovlevich of Voznesensky Street, who “like any honest Russian working man was a terrible drunkard.” Ivan wakes up, tries to eat hot bread baked by his exacting wife Praskovia Osipovna, and discovers upon trying to slice the roll in half that it has “something white” inside. He pulls it out — a nose!

The characters in Gogol dramas always react in perfect deadpan, no matter what weird, unlikely, or impossible inventions the author hurls at them. Though Praskovia viciously berates Ivan for having sliced off one of his customers’ noses, it comes off as routine nagging. The barber, who like many Russian men fond of drink is terrified of his physically mighty wife, slinks toward one of Petersburg’s many bridges at her insistence, with the aim of disposing of his secret shame. En route he tries to figure out what’s happened to him, but quickly checkmates himself mentally, concluding with a frown: “Bread is a thing that is baked, while a nose is something quite different.”

Finally he reaches a bridge and flings the nose in the Neva river, only to turn around and find a police inspector of “respectable appearance with full whiskers” who proceeds to interrogate him… but here again Gogol violates convention, blowing off the scene’s ending, saying, “the incident is absolutely veiled in obscurity, and nothing is known of what happened next.”

In this first section about Ivan Yakovlevich the nose appears, nose-sized, in hot bread, then gets flung in a river, but a sentence later Gogol starts down a different path that will end with the nose in human dimensions, riding carriages, carrying a sword, assuming high civil service rank, and not just speaking but declaiming with terrifying confidence in otherwise conventional story dialogue.

None of the physical events agree with one another, but it all somehow still makes absolute sense, a trick of which maybe a few writers in history might have been capable. Gogol manages to suspend disbelief by creating characters in a few lines that across centuries and cultures are as recognizable as members of your own family. This is how he introduces the “hero” of The Nose:

Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov woke up rather early and made a ‘brring’ noise with his lips... Kovalyov stretched himself and asked for the small mirror that stood on the table to be brought over to him. He wanted to have a look at a pimple that had made its appearance on his nose the previous evening, but to his extreme astonishment found that instead of a nose there was nothing but an absolutely flat surface!

It’s a bold move, to build a story around a jackass whose first waking thought is to get a servant to help him check a newly discovered pimple. But who hasn’t met someone like this?

Gogol goes on to describe a main focus of Kovalev’s thinking, women. He talks about how the Major would engage some “pretty little baggage” on the street and tell her to come visit “Major Kovalev’s flat.” Kovalev mostly spends his days seeking out such dalliances, although he “was not averse to marriage, as long as he could find a bride with a fortune of two hundred thousand.” In fact, he has some plans in that direction at the time of the story. But how to pull that off now, with no nose!

He ends up sneaking out of the house with a handkerchief over his face, like a man with a nosebleed, and engages in a long series of slapstick misadventures to try to fix his situation. These include a visit to the police, an enraged letter to an older woman he believed was keeping his nose hostage to force a marriage to her daughter, and a trip to a Petersburg newspaper in hopes of recovering his nose through a want ad.

That last scene is classic Gogol. The newspaper clerk decides on the spot to refuse to print the ad, for fear of being accused of spreading “false rumors” or worse. When Kovalev protests that there’s nothing false about it, the clerk chastises him that one can never be sure. Why, they’d just had a similar case, in which a man came in to that very office, to place an ad for a lost poodle. It turned into a libel case, as it turned out “the poodle was meant as a satire on a government cashier.”

In another scene, Kovalev has a meeting with a doctor, who when given a look at the “absolutely preposterous smooth flat space” in the middle of Kovalev’s face reacts with the same infuriating deadpan. No bedside manner here; the doc prods the spot so hard, he makes “Kovalyov’s head twitch like a horse having its teeth inspected.” After the cursory exam the doctor advises Kovalev not to worry and just carry on sans nose, it being unnecessary from a medical standpoint. “Wash the area as much as you can with cold water,” he says, “and believe me, you’ll feel just as good as when you had a nose.”

In short everyone behaves as they would in normal situations, as fussy, insensitive jerks, and Kovalev almost — almost — is moved to introspection by the futility of these scenes. One interaction looms above all, however.

The Nose in Russian is a three-letter title, Nos. According to legend, the original title was the same letters in reverse, Son, meaning “dream.” I like it better as Nos: this is a more a coherent story than the random neurological gibberish of sleep. Plus it’s more nightmare than dream. The Freudians long ago claimed this story as a castration fantasy, driven by fears of impotence, while others have explained it in terms of Gogol airing out the frustrations of repressed homosexuality.

Who knows? Gogol was a monkey’s fist of neuroses, and each of his terrors probably gets at least a little play in this story. Whatever the “meaning,” there’s no doubt the most terrifying scene comes when Kovalev has to face his own nose. This section comes after Kovalev leaves a coffee-house:

A carriage drew up… out jumped a uniformed, stooping gentleman who dashed up the steps. The feeling of horror and amazement that gripped Kovalyov when he recognized his own nose defies description... It was wearing a gold-braided uniform with a high stand-up collar and chamois trousers, and had a sword at its side. From the plumes on its hat one could tell that it held the exalted rank of state councilor. And it was abundantly clear that the nose was going to visit someone. It looked right, then left, shouted to the coachman ‘Let’s go!’, climbed in and drove off.

The last part is more classic Gogol. A “state councilor” held the fifth of fourteen ranks in the Tsarist civil service of that time, while Kovalev himself was a mere collegiate assessor, the eighth rank, just south of perfectly middling. It’s a small thing, but a normal comic author might have been content with the insight that the nose had to be one rank higher than poor Kovalev. Gogol went for three ranks above, creating a social gap that placed the nose on the exact razor’s edge of social unapproachability.

You can throw Freud or any other psychological guide out the window here and simply enjoy the conundrum Gogol has created. His hero Kovalev is a complete milksop and dandy, a jellyfish with rank. If he had what we conventionally call “character,” a base of faith or philosophy or any other species of inner fortitude, we could imagine Kovalev approaching the problem of his escaped nose with more courage and confidence. Of course, that kind of person wouldn’t be in this kind of story.

This hero has exactly nothing inside, so what he sees on the street is just a collection of pucker-inducing details: the higher rank, the sword, the hat-plumes, and the aristocratic confidence with which the nose barks at his coachman. Kovalev’s terror only grows when he sees the nose walk into the Kazansky Cathedral, one of the grandest structures in St. Petersburg, a colossal church whose sweeping colonnades and shimmering marble are designed to emphasize the pitiful smallness of man compared to his Creator. Kovalev, for a moment playing Sam Spade or Phil Marlowe, trails the nose into this imposing structure, and is dismayed to find it “standing by one of the walls to the side”:

The nose’s face was completely hidden by the high collar and it was praying with an expression of profound piety.

What’s a human jellyfish to do? He approaches the praying figure, who angrily demands Kovalev explain himself, at which point the Major unfurls his best version of plan: mumbling, making a ploy for class solidarity by dumping on a commoner, followed by name-dropping and pre-surrender:

Of course, I am, as it happens, a Major. You will agree that it’s not done for someone in my position to walk around minus a nose. It’s all right for some old woman selling peeled oranges on the Voskresensky Bridge to go around without one. But as I’m hoping to be promoted soon…Besides, as I’m acquainted with several highly-placed ladies: Madame Chekhtaryev, for example, a state councillor’s wife…you can judge for yourself…

When the nose snaps at him again, correctly observing that Kovalev hasn’t made anything clear at all, Kovalev finally blurts out: “You are my own nose!”

The nose “looked at the Major and frowned a little,” then bullseyed a response:

‘My dear fellow, you are mistaken. I am a person in my own right. Furthermore, I don’t see that we can have anything in common. Judging from your uniform buttons, I should say you’re from another government department.’

With these words the nose turned away and continued its prayers.

It’s one thing to wake up without a nose and find oneself forced to sneak through town with a hanky over one’s face, and something else to see your nose booming around the capital in hot threads. But it’s nuclear-level humiliation to not only be told off by your own body part in an Orthodox church, but take it. Of course one can appreciate things from the nose’s perspective: having at last bust out of the Alcatraz of nasal service, who would voluntarily return to a life in the middle of this goofball’s face?

A parody deus ex machina resolves all. The same policeman from the first scene arrives at Kovalev’s home and delivers the nose, which he caught trying to escape on the Riga stagecoach (it was trying to flee the country!). “I mistook it for a gentleman at first,” says the patrolman. “Fortunately, I had my spectacles with me so I could see it was really a nose.” From there Gogol — who, remember, wanted nothing more than to be celebrated by the Tsar as Russia’s own Titian or Leonardo — can’t help himself and describes exactly what the hero officer would have said, in resonse to being offered tea:

‘I’d like to, but I’m expected back at the prison…The price of food has rocketed…My mother-in-law (on my wife’s side) is living with me, and all the children as well; the eldest boy seems very promising, very bright, but we haven’t the money to send him to school…’

Kovalyov guessed what he was after and took a note from the table and pressed it into the officer’s hands.

Ask anyone who’s ever dealt with Russian traffic police if The Nose needs updating in the area of bribe-seeking language. One of the reasons Russians love Gogol so much is the national everyday life (buit) he describes is still exactly like his stories. In Russia you still find Gogolian taxi drivers, trainmen, “little Tsars” in cloakroams and customs desks, all over, and they all still speak using the same quirky language full of unnecessary filler-words and phrases (“You see yourself… as it seems…”) Gogol had such an incredible ear for.

Americans mostly know Russia as a home of ice, political villains, and intercontinental weaponry, but on the inside it’s a deeply weird place that runs on rhymey nonsense language, oddball superstitions, and an endless parade of strange social micro-transactions, many of them bent in some way. Gogol captured all of this perfectly. Russians will be talking like Gogol characters for the next 500 years.

There’s one last hurdle before The Nose can end. The officer has returned the (once again nose-sized) nose, but Kovalev has no idea how to get it back on his face. He tries several things, calls the aforementioned doctor, but nothing works. No problem: Gogol just presses “fade out to black” on iMovie, writes, “Here again the whole incident becomes enveloped in mist,” and has Kovalev wake up the next day with the nose back on his face. Of course the hero immediately goes out and starts chasing tail and abusing people of lower rank again.

If there’s such a thing as literary love at first sight, I experienced it with The Nose. Though I still adore it, it’s humorous to note had a devastating effect on my life. After reading it in high school, I became convinced a person could create great literature just by locking oneself in a room and devising silly situations. I went on to spend most of my late teen years trying to do just that, at the end of which I ironically turned into the same kind of infuriating helpless hypochondriac-depressive Gogol was. Fortunately, being introduced to this author eventually also led me to leave my room and go across the world to study in his native St. Petersburg, the geography of this story. That had better results.

Gogol was endowed by the God he feared so much with an awesome talent, on par with Tolstoy or Pushkin, but some critics were fooled into thinking the stops and starts and abandoned tunnels of his narratives were evidence of laziness or inattention. Really he had a master con artist’s command of plot that employed subtle misdirections and manipulations of time to lull readers into buying his fun-house landscapes as real.

In The Nose, it adds up to a story that’s both totally absurd and totally believable, creating what may be the densest collection of out-loud laughs in fiction. Gogol was as troubled as people get, but wrote funny stories to cheer himself up. He never seemed happier than he was here.

I can't wait to read this story! I found a PDF of it online after you mentioned it on the podcast a few weeks ago. As a huge fan of Kafka's work, I couldn't help but wonder if he was partially inspired by it when writing "The Metamorphosis" due to the similarly absurd circumstance discovered upon waking.

I looked it up on Wikipedia and found that Kafka "considered Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Gustav Flaubert, Nikolai Gogol, Franz Grillparzer, and Heinrich von Kleist to be his 'true blood brothers'". So, I'm thinking 'yes'.

I'm in the middle of reading an interesting piece that contrasts the two of them here: https://thirdtriumvirate.wordpress.com/2018/08/24/on-gogol-and-kafka/

It thought this quote from R. Karst that is discussed in the piece to be an interesting way to contrast their approaches:

"The basic difference is that Kafka makes illusion real while Gogol makes reality illusory—the former depicts the reality of the absurd, the latter the absurdity of the real”

When I studied in Moscow, we went to an opera based on “The Nose.” It was pretty amazing.